Health and Health Care in the Nations Prisons: Issues, Challenges, and Policies

Contents:

Chronic mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are associated with a high probability of incarceration, but in prison, mentally ill inmates are not guaranteed sustained medication. The problem is particularly acute in jails, as a jail-stay is often temporary but can be prolonged for up to 23 months. In prisons too, being denied counseling and medication can have adverse effects, such as intensifying altercations between inmates and correctional officers, as well as among inmates themselves.

Percentages of mental health care. National Institute of Mental Health. This threat of being denied medication due to limited health care access extends beyond mental health.

The case of Ashley Diamond, a year old transgender woman, illustrates another issue with prison health services. The Justice Department declared formal support for Diamond, agreeing that the hormone therapy was necessary medical care.

While Diamond has since been released from prison, no tangible change in her medication manifested during her sentence, which represents how stark deviations on the inside can be from federal standards. One caveat to the problem with prison health care is that increasingly more prison health care systems are privatized. Not only did existing health care companies see the profitability in providing a service for which the need is rapidly increasing, but also large, correctional health care providers have been established to cater specifically to this sector [12].

As of , over 20 states have switched over to private health care operations in their prisons as a cost-cutting measure. In hiring companies over individual medical professionals, states do not have to provide benefits and pension costs to state workers. While economically defensible, the quality of services provided by these private companies is under investigation not only by human rights groups, but also by federal judges, who have presided over numerous cases centering on poor medical care.

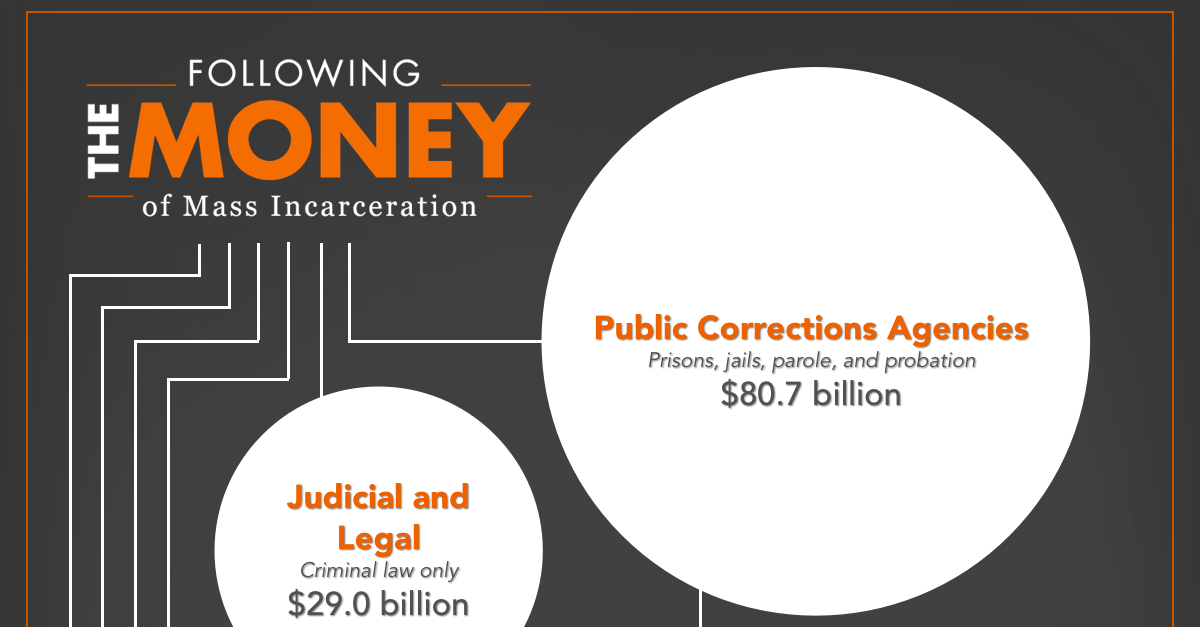

Moreover, the health care spending for states is actually increasing — which is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to this complex issue. Increased spending has vast implications, as expensive prisoner maintenance continues to burden states and private care, while often inadequate, represents a cheap option. Increase in prison health care spending in dollars.

How Health Care Reform Can Transform The Health Of Criminal Justice–Involved Individuals

The Pew Charitable Trusts. If costs are still high, why privatize? Established 35 and 23 years ago, respectively, Corizon and Wexford currently serve a combined total of correctional facilities across the country. Medical treatment in California facilities has been found to be inadequate for the past six years, necessitating federal oversight of the state-run system. Committed to cost control and integrated care, private prison companies outwardly represent the constructive future of correctional health care.

In practice, however, these companies have run into trouble over their inhumane treatment of inmates. In Idaho, Corizon was accused of negligence and poor medical care by a federal judge. In Illinois, numerous inmates have reportedly accused Wexford of insufficient care. While the list of cases and complaints goes on, the lack of competency in prison health care is cause for concern when neither private companies nor the state provides a viable option.

The Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights recognizes this problem, listing on their website a resource guide on medical care. More controversial than the installment of private correctional care companies in state facilities is the role of private health care in private prisons. Together, these private companies run over federal correctional facilities under contracts.

The responsibilities of private companies to their shareholders directly conflict with federal standards, as companies often spend as little as possible to maximize margins.

Editorial Reviews

Health care is one area in which costs are kept particularly low to make this sort of revenue possible. Although CoreCivic does not disclose a number for its health care spending, long-term studies of American prisons suggest that health care is often the second-largest expense of all prisons after staff [20].

When they can, private prison companies like CoreCivic avoid taking inmates over 65 or with chronic illnesses [21]. They also provide essential background information on the development of today's crisis by tracing the history of the U. Read more Read less. Prime Book Box for Kids. Review The book presents a thorough discussion regarding the concerns among health care professionals within the correctional setting about the equality of health care given to the incarcerated population.

Be the first to review this item Amazon Best Sellers Rank: Related Video Shorts 0 Upload your video. Customer reviews There are no customer reviews yet. Share your thoughts with other customers. Write a customer review. Amazon Giveaway allows you to run promotional giveaways in order to create buzz, reward your audience, and attract new followers and customers. Learn more about Amazon Giveaway. Health and Health Care in the Nation's Prisons: Issues, Challenges, and Policies. Set up a giveaway. Health outcomes resulting from such shortages were highlighted in testimony in the Supreme Court case Brown v.

All prisoners are supposed to be screened for suicide risk and medical history at admission, and most of them receive such screenings at most correctional facilities. However, far fewer prisoners receive postadmission medical exams and diagnostic blood tests. Moreover, few data are collected on whether the appropriate treatment is provided once a prisoner is diagnosed with a condition.

This is especially true for substance abuse disorders.

By one estimate, 70—85 percent of state prisoners were in need of drug treatment, while only 13 percent actually received care. General conditions of confinement in prisons and jails also have health consequences. For people living especially chaotic lives, incarceration can provide a stable environment with regular meals; reduced access to alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes; and increased access to health care. In fact, 40 percent of inmates are first diagnosed with a chronic medical condition while in prison. Incarceration presents an important public health opportunity to screen and treat the medically disenfranchised.

However, incarceration rates have long since surpassed the threshold estimated at — per , residents at which the negative effects of imprisonment on both public health and public safety outweigh any positive effects of increased screening and treatment. Diversion to drug and mental health courts, which generally try to solve problems for their clients, has been shown to both improve treatment retention and reduce recidivism.

Improving Care Within Correctional Facilities Correctional health care is integral to community health care. Correctional health care is unlikely to improve unless the barriers that currently separate correctional and community providers are reduced.

Health and Health Care in the Nation's Prisons

The enactment of the ACA provides an important opportunity for more general discussions about improving health services in the United States. Taking full advantage of this opportunity will require community and correctional providers to work together. Correctional providers can advocate for their patients by drawing attention to inadequate resources for appropriate testing and treatment and other conditions that compromise health or care delivery, including poor sanitation and excessive use of force.

At the same time, the broader health professions should leverage their traditional moral authority into civic engagement on behalf of their collective patient body, which includes prisoners. For example, the health professions, through their professional societies, could push for legislative initiatives to improve transitional care programs for prisoners.

The State Of Correctional Health In The United States

The support of the health professions may help correctional and public officials emphasize the importance of improving the quality of health care not only during incarceration but after releasees return to the community. Improving correctional care and postrelease outcomes will also require improving systems of external oversight and quality management, including appropriate definitions of quality of care.

The current lack of standardized data collection and reporting makes it almost impossible to determine the extent and quality of correctional health care across the country. Increased oversight and accountability are particularly important given the expansion of privately owned correctional facilities and the contracting of correctional health services to private companies. Incorporating correctional health into community health care quality measures may create an atmosphere of joint responsibility between the public health and safety systems.

Three specific structures may be especially conducive to increasing the oversight and quality of correctional care.

The first is that the ACA may provide opportunities to incorporate correctional health into accountable care organizations ACOs. These networks of doctors and hospitals are offered incentives to work together to simultaneously improve care and reduce costs for Medicare and Medicaid recipients. ACOs must meet specific quality benchmarks that emphasize prevention, and they additionally receive bonuses for cost containment. Incorporating correctional health services into this framework may be especially relevant given the growing size of the older correctional population, most of whom will eventually enter Medicare upon their release.

Reminding community-based providers that these patients are likely to return to their care may provide incentives for them to extend the boundaries of existing ACO models. Second, increasing the use of a risk-needs-responsivity RNR model appears likely to improve criminal justice outcomes, facilitate greater attention to data collection, and optimize triaging of the type of care individuals receive. It uses criminal justice history, unmet psychosocial needs such as mental illness, and targeted interventions to match releasees to programs most appropriate to their risk level.

- Underdogs.

- Dante and Derrida: Face to Face (SUNY series in Theology and Continental Thought).

- Product details.

- Issues, Challenges, and Policies.

- Background!

As a guide to service delivery, the RNR model has been associated with positive outcomes including reduced recidivism, and its focus on behavioral change indicates potential improvement in health outcomes as well. Finally, instituting accreditation of correctional health care services and facilities could provide a more direct means of enforcing quality measurement and oversight.

Correctional facilities currently have the option of voluntary accreditation from the American Public Health Association, the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, and the American Correctional Association, among others , but there are generally no consequences for violations or lapses of accreditation. An expectation for all correctional facilities to become and remain accredited, with clear-cut consequences for lapses, would provide a possible mechanism to measure standards and improve performance. Increasing Access To Community-Based Care Improving the quality of correctional health care is only part of the solution to improving the quality of care to this vulnerable population.

A second set of activities must focus on improving access to high-quality, community-based care. Appropriate medical and behavioral health treatment services have the potential to improve individual and community health while simultaneously reducing recidivism. The ACA provides an invaluable foundation but not a complete solution. Most evidently, the ACA will increase access to health care for people released from incarceration by reducing the financial barriers through the expansion of Medicaid currently in about half of the states and subsidized health insurance through the Marketplaces, or exchanges.

Lack of insurance has been a major obstacle to health care for criminal justice—involved populations. Correctional staff can identify people eligible for coverage and help releasees complete the process of enrolling in an exchange or in Medicaid. This may help alleviate the detrimental effects of the current practice in many states where state insurance is terminated rather than suspended upon incarceration.

In addition, ways to share health care costs at the federal, state, and local levels should be explored to optimize services. However, there are multiple barriers to care beyond the lack of insurance. Many releases struggle with housing, employment, and personal relationships, and health issues become a low priority. The lack of coordination between criminal justice and public health organizations also creates obstacles to care, especially at transition points—including return to the community— where medical information may not follow.

The mental health and addiction treatment needs of some complicate their reentry into the community by posing a barrier to access to health care and treatment for other health needs. For many with active, untreated mental illnesses or addiction, they are unable to engage in health care, make appointments, or participate in a treatment plan or other activities that can optimize health care. This provision has the potential to increase the use of health care and reduce incarceration and recidivism by treating these common underlying conditions.