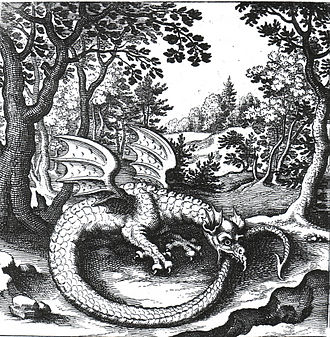

The Snake, The Dragon and The Tree

Contents:

When the villagers charged in, they found two huge, chocolate-brown adult dragons, each as big around as an oil barrel. With them was a smaller dragon, the width of a coconut palm, which was colourful and had a yellow belly. In retaliation for the killings, the people cut the two adults in half.

But they spared the young dragon, believing it to be innocent. They also made an agreement with it that is still binding today: Later, the people returned to less remote villages. But they say the dragons are still around. View image of The Burak river in Borneo, home of mysterious dragons Credit: I first heard this story in late July , when I sat by a fragrant campfire listening to Pak Rusni, an elder from the Dayak village of Tumbang Tujang, recount his ancestral tale. Rusni is 54 years old, with gentle, dark eyes. He mostly spoke softly, and the cicadas threatened to drown out his words.

But when he got to the crux of the tale, Rusni became loud and animated. He drew me a diagram depicting the dragon den, the tunnel, and the riverbank settlement. And then he gestured upriver. Our campsite was near the northern border of Indonesian Borneo, along the Burak river. If we journeyed upriver for another day and a half, Rusni said, we would find the remnants of the village besieged by dragons.

Fascinated by Rusni's story, I wanted to find out which of the local snakes might be closest to the dragons of the story. So many centuries later, I didn't expect to find a definitive answer. But there were two questions that I could nail down, which might offer pointers. Were there any snakes in Borneo that grew so monstrously large? And could any kill children that quickly?

View image of Borneo is a hotspot of biodiversity Credit: I soon realised there were many possible culprits. The Borneo rainforest is million years old, one of Earth's oldest, so its inhabitants have had plenty of time to diversify.

What's more, during the last ice age land bridges linked Borneo to mainland Asia and other Indonesian islands. Species emigrated from the mainland to the islands, seeding Borneo with an astonishing array of organisms. When the ice age ended, flooding the land bridges, Borneo's creatures were free to evolve in relative isolation. The snakes are particularly diverse.

Was Adam really dumbstruck by a silly little talking snake?

There may be about species on the island, possibly more. Some live underground, others in the leaves littering the forest floors. Some surf through the treetops, flying from tree to tree. Others prefer to live underwater, or in caves. Many use the structures built by humans: Several are dangerous to humans.

BBC navigation

I was told the locals sometimes refer to our field site as the "Land of the Man-Eating Snakes": So before we set out, I asked our expedition leader Peter Houlihan , of the Barito River Initiative for Nature Conservation and Communities , which local snakes were most deadly. He was not reassuring. View image of At least there aren't any black mambas: Since they first appeared between and million years ago, snakes have evolved rapidly.

A lot of that has gone into creating new ways to kill other animals, in particular snakes' infamous venoms. That variety might be a response to the challenges involved with living life as a tube. So to ease the strain of hunting without limbs, snakes have developed highly specialized ways of killing things — ways that could, conceivably, account for vanishing village children.

View image of Warning: Snake venoms contain a bewildering array of proteins that work together to bring down prey. Some, like king cobra venom, have more than different kinds. These toxic cocktails are hugely variable. Not only do different species produce different mixtures, but snakes of the same species can mix different drinks as well. What's more, a snake's venom may change as it ages. This might be the result of an evolutionary arms race, with venom mixtures evolving to work best on each snake's most common prey.

Alternatively, it could be that some snakes have evolved a range of toxins that lets them bring down different types of prey. Scientists are just beginning to trace the evolutionary history of the serpents' deadly potions. But it is clear that the genes coding for snake venom proteins have evolved rapidly. Last year McCleary, Pollock and their colleagues published the sequence of the king cobra genome , and found that base pairs were being swapped and shifted unusually often.

The Snake, the Dragon and the Tree, by John Layard, Kitchener, Carisbrooke Press,. , pp., US$ (paperback), ISBN: In Norse mythology, Níðhöggr is a dragon/serpent who gnaws at a root of the world tree, These are names for serpents: dragon, Fafnir, Jormungand, adder, Nidhogg, snake, viper, Goin, Moin, Grafvitnir, Grabak, Ofnir, Svafnir, masked one.

So which of Borneo's snakes might be capable of killing a small child? Here are the prime suspects. The red-headed krait Bungarus flaviceps is elegant but deadly. Its shiny black body is bookended by a bright red head and tail.

Krait venoms disable their prey's nervous system. They block the junctions that convey messages from nerves to muscles, making it impossible to breathe or move. In , a many-banded krait in Myanmar bit herpetologist Joseph Slowinski on the hand. Too far afield to find proper medical attention, he died in just over a day. But kraits don't fit the profile of dragons. Red-headed kraits can be two metres long, but they are thin, and the dragons were fat.

Plus, kraits are sluggish in the day.

Serpents in the Bible

Most bites happen at night, when the snakes stay near a sleeping human for warmth. Take the Malayan blue coral snake Calliophis bivirgatus , a nocturnal blue serpent with a bright red belly. As with other snakes, the venom gland begins behind the eye. But it stretches for more than a third of the snake's length, which can reach 1. That means a blue coral snake's venom gland could be longer than your foot. But despite their humongous venom glands, coral snakes aren't even close to being dragons. They hide among the leaves littering the ground, and mostly eat other snakes — often small, burrowing ones.

That means their fangs are too small to easily pierce human skin. View image of King cobras can rear up off the ground Credit: Now this looks more like it.

- Navigation menu.

- Not Prepared to Donate?.

- Dangerous Passion (Dangerous series).

- The Consolidation of Dictatorship in Russia: An Inside View of the Demise of Democracy (Praeger Secu.

Deities and other figures. Norse gods Norse giants Mythological Norse people, items and places Germanic paganism Heathenry new religious movement. The cosmological tree Yggdrasil and its inhabitants in Norse mythology. Sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology Norse cosmology. Retrieved from " https: Creatures in Norse mythology European dragons Legendary serpents. Articles lacking in-text citations from February All articles lacking in-text citations Articles containing Old Norse-language text Articles containing Icelandic-language text Articles containing Danish-language text Articles containing Norwegian-language text Articles containing Swedish-language text.

Views Read Edit View history. In other projects Wikimedia Commons.

Accessibility links

This page was last edited on 4 September , at By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. A hall I saw, far from the sun, On Nastrond it stands, and the doors face north, Venom drops through the smoke-vent down, For around the walls do serpents wind. I there saw wading through rivers wild treacherous men and murderers too, And workers of ill with the wives of men; There Nithhogg sucked the blood of the slain, And the wolf tore men; would you know yet more?

A hall she saw standing remote from the sun on Dead Body Shore. Its door looks north. There fell drops of venom in through the roof vent.

- FINDERS?

- Virgin Star.

- Serpents in the Bible - Wikipedia!

- Local Partners.

That hall is woven of serpents' spines. She saw there wading onerous streams men perjured and wolfish murderers and the one who seduces another's close-trusted wife. There Malice Striker sucked corpses of the dead, the wolf tore men. Do you still seek to know? From below the dragon dark comes forth, Nithhogg flying from Nithafjoll ; The bodies of men on his wings he bears, The serpent bright:

- Lung Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management (Current Multidisciplinary Onc

- Soil Erosion and Carbon Dynamics (Advances in Soil Science)

- Medicina Basada en Cuentos V2 (Spanish Edition)

- The Road to Big Week: The Struggle for Daylight Air Supremacy Over Western Europe, July 1942 – Febru

- Pray For The Lost: Impact The Eternal Destiny Of Those You Love Through Prayer