Humanitarian Intervention: The Case of Kosovo and Ruanda

Contents:

If the West were truly committed to the creation of a world system where respect for humanity was of the highest order, we would take notice of other regions of the world where regimes have engaged in heinous crimes against humanity. Unfortunately, the West has ignored many of these cases. In Rwanda in , approximately , Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed in one of the most horrendous examples of genocide since World War II. Two million people fled the country as refugees. The conditions that produced genocide in Rwanda were remarkably similar to those that led to humanitarian violations in Kosovo.

A deteriorating political and economic situation led those who sought to maintain their hold on power to brand a group of people as the "scapegoat," which became the target for physical attack and murder. The international community failed to respond.

- .

- !

- Social Psychology.

- A Friend Up In the Clouds.

Dominant powers actually resisted effective UN action, and it took over a year for President Clinton to admit that genocide occurred. For the past 50 years, the majority of those lawyers, activists, survivors, politicians, and other public figures collectively termed "human rights practitioners" have maintained that such crimes demand justice on a correspondingly massive scale. Beginning with Nurem berg's designation of "crimes against humanity," human rights practitioners have labored—from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Con vention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide in and the Geneva Conventions, to UN-sponsored tribunals for Rwanda and Bosnia and the International Criminal Court drafted this July in Rome—to expand our moral and legal understanding of criminality.

Only by extending the metaphor of criminal justice beyond borders, goes the dominant strain of thinking in the human rights community, can we truly make human rights universal; only by punishing perpetrators, goes the corollary, can a nation emerging from a period of genocide or mass violence hope to reestablish the rule of law and prevent future horrors.

Aryeh Neier's War Crimes: Brutality, Genocide, Terror, and the Struggle for Justice falls squarely within this tradition. Neier, a distinguished human rights activist and a founder and former executive director of Human Rights Watch, has labored long and hard both for the protection of human rights and, more broadly, against the world's frequent indifference to them. Like many of his colleagues around the world, Neier believes first and foremost in the principle of accountability: It is his view that all the human rights treaties and tribunals created since World War II represent "a half-century struggle for accountability—imperfect, passionate, yet rooted in law and universal principles.

But his overriding theme, stated early on, is that justice is best served through "the disclosure and acknowledgment of abuses, the purging of those responsible from public office, and the prosecution and punishment of those who commit crimes against humanity.

Who can argue against justice? Those who demand accountability have the advantage of being morally unassailable. But by all accounts, none of the three pre multilateral conventions dealing with torture, genocide, or human rights did much to discourage either the Bosnian Serb or Croatian ethnic cleansing campaigns during the ensuing Balkan war; similarly, the existence of the ICTY, which in recent years has had some notable success in bringing Bosnian Serb foot soldiers and some unit-level officers into custody, does not appear to have affected the course of the Serbian campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo—except, perhaps, to encourage Serbian soldiers to execute Kosovars more surreptitiously.

T he existence of the Yugoslav tribunal, in short, has been little hindrance to the Serbian campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. It is this question that human rights practitioners like Neier have failed to answer honestly. Yet Neier himself cites example after example of Western nations ducking their obligations to intervene in clear cases of genocide and human rights abuse. As Neier knows better than anyone, gross human rights abuses frequently go unpunished not because of vague treaty language, but because human rights enforcement is rarely the first priority of the potential intervener; the problem lies with states' commitment to the principles of human rights enforcement, not with the principles themselves.

Indeed, the existing multilateral conventions on torture, genocide, and human rights provide ample legal basis for a concerned state—or an activist judge, as in the Augusto Pinochet case—to intervene, or to hold perpetrators accountable.

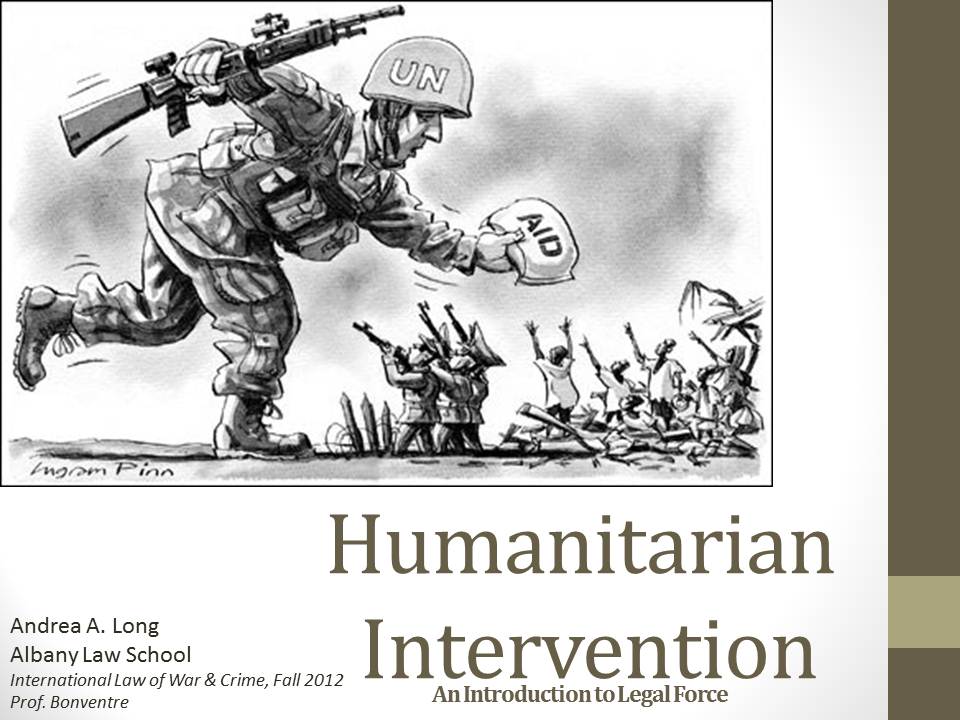

There can be little doubt that the media plays a major role in mobilizing public, and thus political, support for humanitarian interventions. The second charge with regard to establishing dangerous precedents is that it is open to abuse or selectivity. The danger does not lie in the arbitrary appeal to high principles: With this in mind, it is now necessary to look specifically at the case of Rwanda to determine if the embryonic norm of humanitarian intervention was advanced and what other obstacles may have prevented international action. While there may be no just war, there are necessary and unavoidable ones.

Moreover, the only truly successful efforts this century to impose the rule of international law on transgressor nations—in postwar Japan and Germany—each required a lengthy occupation by Allied troops and an extensive process of victor-imposed institutional reform. In both cases, the kind of international criminal justice Neier envisions included an element not found in the two existing UN tribunals or the nascent International Criminal Court ICC: In an anarchic international system, states tend to enforce human rights not only when, but also to the degree that, it suits them.

Both problems have been illustrated repeatedly since , when Cold War strategic imperatives ceased to obstruct intervention by concerned nations. The same year that saw the breakup of the Soviet Union witnessed the onset of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, the first clear test of "never again" Western internationalism—as it turned out, a test NATO and the United Nations failed miserably. In , the world stood by as genocide unfolded again, this time in Rwanda, with the foreknowledge of Belgium, France, the United States, and the UN.

The situation in Kosovo is only slightly better. A dedicated program of air bombardment is certainly better than nothing, but what if, as most observers outside the NATO establishment assert and as all previous experience indicates, halting the Serbian program of ethnic cleansing requires the use of ground troops? In the cases of Bosnia and Rwanda, those countries in the best position to prevent genocide were unable to muster the political will necessary to do so in any significant way; in Kosovo, Western leaders ruled out the use of NATO ground troops almost as soon as the fighting began.

As of this writing in early May, the prospect of a wholesale Allied occupation appears distant. It is a lesson that the Serb ian leadership has learned well. And although Neier never says so outright, it's clear that the main reason he and most other human rights practitioners want a permanent, independent international court is that it would take the decision to punish genocide and mass violence out of the hands of certain irresolute governments with permanent vetoes on the Security Council. Pretending otherwise is a necessary subterfuge, of course, and Neier's desire to establish a truly independent and impartial international tribunal is a thoroughly noble and understandable one.

Genocide is so massive a crime that, as Hannah Arendt once wrote of the Holocaust, it "oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems. But a deeper problem may be that tribunals—and the paradigm of retributional justice they represent—are simply an inadequate response to mass violence and its aftermath.

- Humanitarian Intervention: Iraq, Afghanistan, Kosovo, Rwanda.

- Rwanda, Kosovo, and the Limits of Justice;

- You may also like.

- How Not to Date.

- The Center for Public Justice!

- NIKOLAI IVANOVICH KIBALCHICH: Terrorist Rocket Pioneer!

The Yugoslavian tribunal failed not simply because such tribunals are bound to fail, but because it did nothing to address the root causes of the genocide. Ethnic cleansing in the Balkans is not a consequence of lawlessness. Rather, the deep divide between Serbs and Kosovars has its roots in a deliberate, decade-long effort by Serbian leaders: First, to mobilize what was then a largely dormant ethnic passion as a vehicle for political hegemony within the former Yugoslavia; and second, to provide a target for Serbian nationalism by demonizing Bosnian Muslims and, later, Albanian Kosovars.

It is often pointed out that Milosevic, once a Com munist Party apparatchik, launched his career as a demagogue by stirring Kosovo Serb fears of an Albanian "demographic genocide"—a reference to the high birthrate of ethnic Albanians that would, according to state propaganda, eventually force ethnic Serbs out of the cradle of Serbian civilization.

Like all such ethnic entrepreneurs, Milosevic incorporated shards of ancient and recent history into a potent nationalist vision, a semi-mythological account of the Serbian nation that shrewdly played upon what many observers have described as a national sense of victimhood. Although Neier's book includes a substantial discussion of Balkan history , he pays too little attention to the process of ethnic mobilization in post-Tito Serbia.

For instance, in recounting the ancient Otto man defeat of the Serbs in , Neier takes at face value the claim that it was a "defining moment in Serb history. Indeed, there was no significant debate over truth. But the "truth" is far more than the details of who was killed or raped where and by whom, and in the cases of both Bosnia and Rwanda, the "history" that Neier takes for granted was constructed for purely political purposes through fascist methodologies that are by now familiar.

Kosovo and Rwanda: Selective Interventionism?

A quick look at the academic understanding of intervention in Kosovo at the time, however, suggests that debates regarding the legitimacy of war were just as heated then as they are now. The objection that one cannot intervene in Kosovo, because there was no intervention in Rwanda and elsewhere, conveys a valid accusation, but it would be absurd to conclude that action in Kosovo is prohibited.

Such a prohibition would amount to the cynical axiom that the terrible failure of the world community in Rwanda necessitates a duty to further failures. While the increased misery of the refugees in the context of the bombings tempted me to side with the anti-interventionists, in the end their arguments turn out to rely on intellectual and moral self-deception. In principled terms, the dispute between violence and non-violence is clear.

Access Check

While there may be no just war, there are necessary and unavoidable ones. Well before the massacres in Bosnia, it was clear that one does not remain innocent if one refrains from offering timely opposition to dictators and tyrants, if necessary with force. Schneider comes out entirely in support of the war.

Humanitarian intervention: the case of. Kosovo. Book section. Original citation: . The creation of the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals, the. Could the air campaign be considered as lawfiil humanitarian intervention? e) The deterioriation of the situation in Kosovo and its magnitude constituted a se .. Foreign forces entered Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti, and Albania on explicit authori.

But that he has to come out in such full-fledged support of war suggests there was no general consensus at the time. The hypothesis of a disinterested humanitarian motivation is untenable, however appalling the large-scale use of violence by Serbs to drive out defenseless people from their homes in Kosovo. When all is said and done, Western indignation at the violation of human rights is no less selective than in the past.