Demosthenes: Statesman and Orator

Contents:

Philip advanced into Chalcidice , threatening the city of Olynthus , which appealed to Athens. Finally, Philip and the Athenians agreed in April to the Peace of Philocrates ; Demosthenes, partly to gain time to prepare for the long struggle he saw ahead, agreed to the peace and went as one of the ambassadors to negotiate the treaty with Philip.

Meanwhile, Philip continued his tactic of setting the Greek city-states, such as Thebes and Sparta, against each other. Demosthenes was one of several ambassadors sent out on a futile tour of the Peloponnesus to enlist support against Philip.

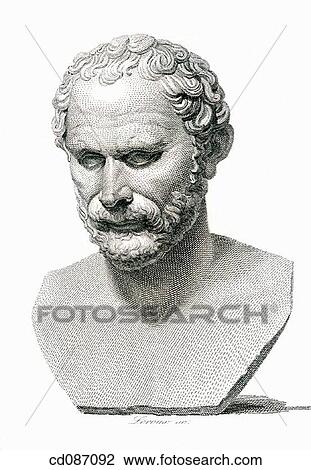

- Statue of Demosthenes, a Greek statesman and orator of ancient Athens. Isolated on white.

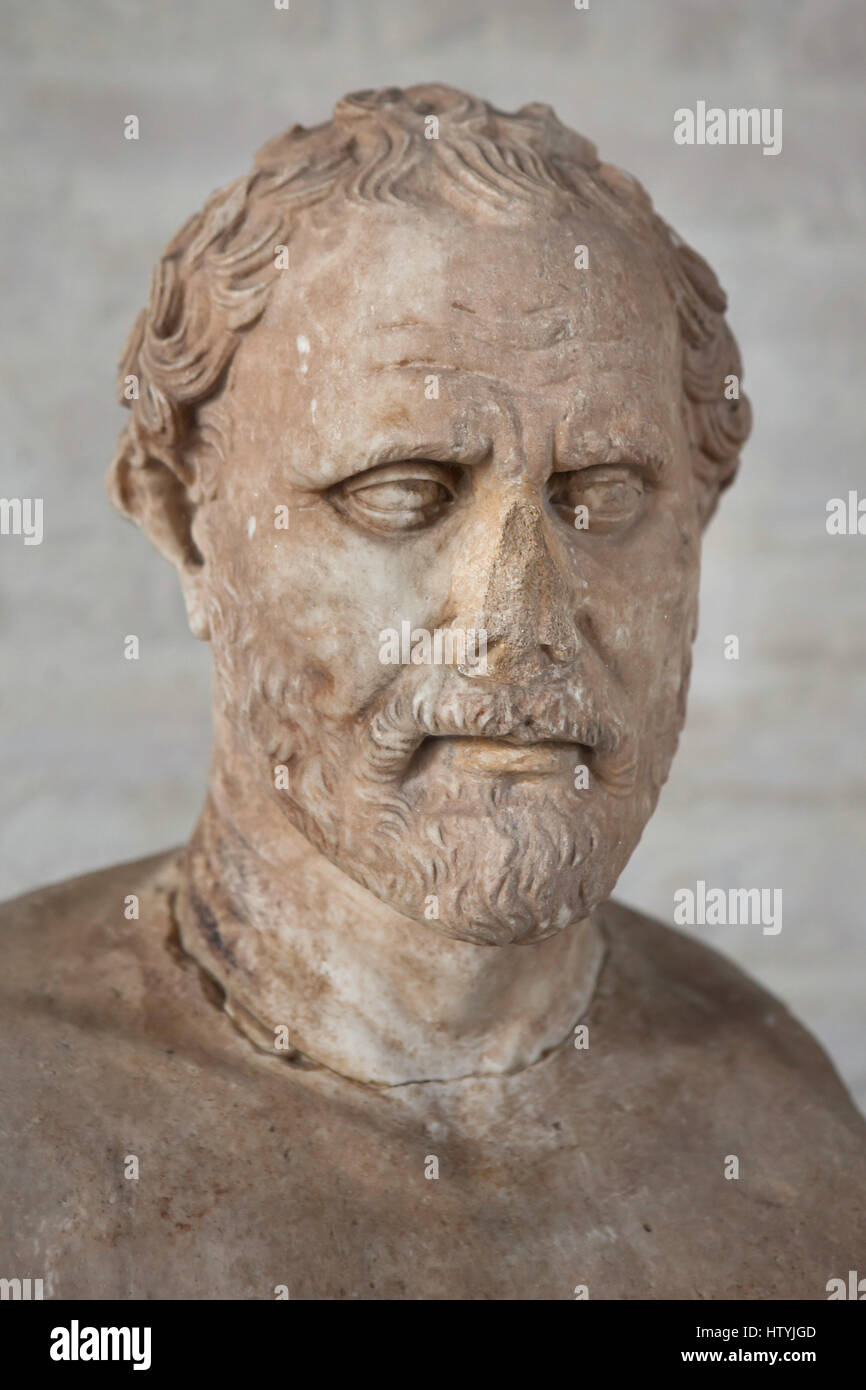

- Demosthenes ( BC) was a prominent Greek statesman and orator Stock Photo: - Alamy?

- Item Preview.

- Bryn Mawr Classical Review !

In retaliation Philip protested to Athens about certain statements made by these ambassadors. The court, however, acquitted Aeschines. As a result, Demosthenes became controller of the navy and could thus carry out the naval reforms he had proposed in In addition, a grand alliance was formed against Philip, including Byzantium and former enemies of Athens, such as Thebes.

Indecisive warfare followed, with Athens strong at sea but Philip nearly irresistible on land. Disaster came in , when Philip defeated the allies in a climactic battle at Chaeronea in north-central Greece.

According to Plutarch, Demosthenes was in the battle but fled after dropping his arms. Whether or not he disgraced himself in this way, it was Demosthenes whom the people chose to deliver the funeral oration over the bodies of those slain in the battle.

Was Demosthenes a cynical opportunist or a great patriot? Why is Demosthenes' oratory the best to have survived from classical Greece? The career of. Editorial Reviews. From the Back Cover. Was Demosthenes a cynical opportunist or a great Demosthenes: Statesman and Orator 1st Edition, Kindle Edition.

After the peace concluded by the Athenian orator and diplomat Demades , Philip acted with restraint; and, though the pro-Macedonian faction was naturally greatly strengthened by his victory, he refrained from occupying Athens. Demosthenes came under several forms of subtle legislative attack by Aeschines and others.

In Greece was stunned by the news that Philip had been assassinated. When his son Alexander succeeded him, many Greeks believed that freedom was about to be restored.

But within a year Alexander proved that he was an even more implacable foe than his father—for, when the city of Thebes rebelled against him in , he destroyed it. A string of victories emboldened Alexander to demand that Athens surrender Demosthenes and seven other orators who had opposed his father and himself; only a special embassy to Alexander succeeded in having that order rescinded. Shortly thereafter, Alexander began his invasion of Asia that took him as far as India and left Athens free of direct military threat from him.

In , nevertheless, judging that the pro-Alexandrian faction was still strong in Athens, Aeschines pressed his charges of impropriety against Ctesiphon—first made six years earlier—for proposing that Demosthenes be awarded a gold crown for his services to the state.

The resulting oratorical confrontation between Aeschines and Demosthenes aroused interest throughout Greece, because not only Demosthenes but also Athenian policy of the past 20 years was on trial. A jury of citizens was the minimum required in such cases, but a large crowd of other Athenians and even foreigners flocked to the debate.

As always, his command of historical detail is impressive. Over and over again he asks his audience what needed to be done in a crisis and who did it. Demosthenes and his policies had received a massive vote of popular approval. Six years later, however, he was convicted of a grave crime and forced to flee from prison and himself go into exile.

He was accused of taking 20 talents deposited in Athens by Harpalus , a refugee from Alexander. Demosthenes was found guilty, fined 50 talents, and imprisoned. The circumstances of the case are still unclear.

Demosthenes may well have intended to use the money for civic purposes, and it is perhaps significant that the court fined him only two and one-half times the amount involved instead of the 10 times usually levied in such cases. His escape from prison made it impossible for him to return to Athens to raise money for the fine. The onetime leader of the Athenians was now a refugee from his own people. Another dramatic reversal occurred the very next year, however, when Alexander died. The power of the Macedonians seemed finally broken; a new alliance was concluded against them. The Athenians recalled Demosthenes from exile and provided money to pay his fine.

His former friend Demades then persuaded the Athenians to sentence Demosthenes to death. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance , his name was a synonym for eloquence. Demosthenes in the underworld: Notes Includes bibliographical references and index. View online Borrow Buy Freely available Show 0 more links Related resource Publisher description at http: Set up My libraries How do I set up "My libraries"? These 7 locations in All: Australian National University Library.

Open to the public. The University of Melbourne Library.

Navigation menu

University of Queensland Library. Open to the public ; PA University of Sydney Library. University of Western Australia Library. This single location in Australian Capital Territory: This single location in New South Wales: This single location in Queensland: D68 Book English Show 0 more libraries Demetrius Phalereus and the comedians ridiculed Demosthenes's "theatricality", whilst Aeschines regarded Leodamas of Acharnae as superior to him. Demosthenes relied heavily on the difference aspects of ethos, especially phronesis. When presenting himself to the Assembly, he had to depict himself as a credible and wise statesman and adviser in order to be persuasive.

One tactic that Demosthenes used during his philippics was foresight. He pleaded with his audience to predict the potential of being defeated, and to prepare. He appealed to pathos through patriotism and introducing the atrocities that would befall Athens if it was taken over by Philip. He would also slyly undermine his audience by claiming that they had been wrong to not listen before, however they could redeem themselves if they listened and acted with him presently.

Demosthenes tailored his style to be very audience-specific. He took pride in not relying on attractive words but rather simple, effective prose. He was mindful of his arrangement, he used clauses to create patterns that would make seemingly complex sentences easy for the hearer to follow.

His tendency to focus on delivery promoted him to use repetition, this would ingrain the importance into the audience's minds; he also relied on speed and delay to create suspense and interest among the audience when presenting to most important aspects of his speech. One of his most effective skills was his ability to strike a balance: Demosthenes's fame has continued down the ages. Authors and scholars who flourished at Rome , such as Longinus and Caecilius , regarded his oratory as sublime.

According to Professor of Classics Cecil Wooten, Cicero ended his career by trying to imitate Demosthenes's political role. The divine power seems originally to have designed Demosthenes and Cicero upon the same plan, giving them many similarities in their natural characters, as their passion for distinction and their love of liberty in civil life, and their want of courage in dangers and war, and at the same time also to have added many accidental resemblances.

I think there can hardly be found two other orators, who, from small and obscure beginnings, became so great and mighty; who both contested with kings and tyrants; both lost their daughters, were driven out of their country, and returned with honor; who, flying from thence again, were both seized upon by their enemies, and at last ended their lives with the liberty of their countrymen. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance , Demosthenes had a reputation for eloquence. In modern history , orators such as Henry Clay would mimic Demosthenes's technique.

His ideas and principles survived, influencing prominent politicians and movements of our times. Hence, he constituted a source of inspiration for the authors of The Federalist Papers a series of 85 essays arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution and for the major orators of the French Revolution. However, the speeches that Demosthenes "published" might have differed from the original speeches that were actually delivered there are indications that he rewrote them with readers in mind and therefore it is possible also that he "published" different versions of any one speech, differences that could have impacted on the Alexandrian edition of his works and thus on all subsequent editions down to the present day.

The Alexandrian texts were incorporated into the body of classical Greek literature that was preserved, catalogued and studied by scholars of the Hellenistic period. Friedrich Blass , a German classical scholar, believes that nine more speeches were recorded by the orator, but they are not extant.

Some of the speeches that comprise the "Demosthenic corpus" are known to have been written by other authors, though scholars differ over which speeches these are. In addition to the speeches, there are fifty-six prologues openings of speeches. They were collected for the Library of Alexandria by Callimachus , who believed them genuine.

According to James J. Murphy, Professor emeritus of Rhetoric and Communication at the University of California, Davis , his lifelong career as a logographer continued even during his most intense involvement in the political struggle against Philip.

Search stock photos by tags

According to Libanius, Eubulus passed a law making it difficult to divert public funds, including "theorika," for minor military operations. Burke argues that, if this was indeed a law of Eubulus, it would have served "as a means to check a too-aggressive and expensive interventionism [ Thus Burke believes that in the Eubulan period, the Theoric Fund was used not only as allowances for public entertainment but also for a variety of projects, including public works.

MacDowell, Demosthenes regarded as Greeks only those who had reached the cultural standards of south Greece and he did not take into consideration ethnological criteria. Plutarch argued that Demosthenes accepted the bribe out of fear of Meidias's power. Weil agreed that Demosthenes never delivered Against Meidias , but believed that he dropped the charges for political reasons.

Kenneth Dover also endorsed Aeschines's account, and argued that, although the speech was never delivered in court, Demosthenes put into circulation an attack on Meidias. Dover's arguments were refuted by Edward M. Harris, who concluded that, although we cannot be sure about the outcome of the trial, the speech was delivered in court, and that Aeschines' story was a lie. Aeschines and Dinarchus also maintained that when the Arcadians offered their services for ten talents, Demosthenes refused to furnish the money to the Thebans, who were conducting the negotiations, and so the Arcadians sold out to the Macedonians.

He also narrates the following story: Shortly after Harpalus ran away from Athens, he was put to death by the servants who were attending him, though some assert that he was assassinated. The steward of his money fled to Rhodes, and was arrested by a Macedonian officer, Philoxenus.

Philoxenus proceeded to examine the slave, "until he learned everything about such as had allowed themselves to accept a bribe from Harpalus. Vince singles out five as spurious: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For other historical and fictional personages named Demosthenes, see Demosthenes disambiguation. Bust of Demosthenes Louvre , Paris , France. Battle of Chaeronea BC.

Archived from the original on 4 August Innes, 'Longinus and Caecilius", — Innes, 'Longinus and Caecilius", Weil, Biography of Demosthenes , 5—6. Archived 20 May at the Wayback Machine. Badian, "The Road to Prominence", Archived from the original on 9 March Retrieved 7 May MacDowell, Demosthenes the Orator , ch.

Demosthenes

Cox, Household Interests , MacDowell, Demosthenes the Orator, ch. Nietzsche, Lessons of Rhetoric , —; K. Tsatsos, Demosthenes , Weil, Biography of Demothenes , 10— On the Crown , , note Kennedy, Greek Literature , On The Crown , note On the Crown , Usher, Greek Oratory , Badian, "The Road to Prominence", 29— Harris, "Demosthenes' Speech against Meidias", —; J. Vince, Demosthenes Orations , I, Intro. Worman, "Insult and Oral Excess", 1—2. On The Crown , 9, On The Crown , Badian, "The Road to Prominence", 29—30; K. Habinek, Ancient Rhetoric and Oratory , 21; D.

Phillips, Athenian Political Oratory , Hansen, The Athenian Democracy , De Romilly, Ancient Greece against Violence , — Cawkwell, Philip II of Macedon , — Carey, Aeschines , 7—8. Carey, Aeschines, 7—8, Tsatsos, Demosthenes , ; H. Weil, Biography of Demosthenes , 41— Tsatsos, Demosthenes , —; H. Rhodes, A History of the Classical World , Tsatsos, Demosthenes , — Green, Alexander of Macedon, Hamilton, Alexander the Great , Tsatsos, Demosthenes, ; "Demosthenes". Duncan, Performance and Identity in the Classical World , Droysen, History of Alexander the Great , —; K.

Tsatsos, Demosthenes , —; D.

- stock photos, vectors and videos.

- Freely available!

- Demosthenes :statesman and orator /edited by Ian Worthington. – National Library;

Whitehead, Hypereides , —; I. Worthington, Harpalus Affair , passim. Archived 30 November at the Wayback Machine. Carey, Aeschines , 12— Macaulay, On Mitford's History of Greece, Carey, Aeschines , 12—14; K. Wooten, "Cicero's Reactions to Demosthenes", Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. Jaeger, Demosthenes , — Innes, "Longinus and Caecilius", note Bollansie, Hermippos of Smyrna , Wooten, "Cicero's Reactions to Demosthenes", 38— Archived 29 June at the Wayback Machine.

Nietzsche, Lessons of Rhetoric , — A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. Innes, 'Longinus and Caecilius", passim. Sowerby, "Thomas Wilson's Demosthenes", 46—47, 51—55; "Demosthenes". Gibson, Interpreting a Classic , 1. Rebhorn, Renaissance Debates on Rhetoric , , , Sowerby, "Thomas Wilson's Demosthenes", 46—47, 51— Marcu, Men and Forces of Our Time, Van Tongeren, Reinterpreting Modern Culture , On The Crown , 26; H.

Demosthenes: Statesman and Orator - Google Книги

Weil, Biography of Demosthenes, 66— On The Crown , 26— Gibson, Interpreting a Classic, 1; K. Kapparis, Apollodoros against Neaira, Worthington, Oral Performance , Cohen, The Athenian Nation, Cohen, The Athenian Nation , 76; "Demosthenes". Nietzsche, Lessons of Rhetoric , Archived 29 March at the Wayback Machine.

Tsatsos, Demosthenes, 84; H. Weil, Biography of Demosthenes , 10— Hawhee, Bodily Arts , Rose, The Staff of Oedipus , On the Crown , note Tsatsos, Demosthenes , 90; H. Weil, Biography of Demothenes , Worthington, Alexander the Great , Vince, Demosthenes I, — Harris, "Demosthenes' Speech against Meidias", Harris, "Demosthenes' Speech against Meidias", passim ; H.

Weil, Biography of Demosthenes,

- Public Health Foundations: Concepts and Practices

- The Crusader: Book One of The Crusader Series

- Chantes Song

- The New Welfare Bureaucrats: Entanglements of Race, Class, and Policy Reform

- Humoresque No. 5 in A Minor - from Humoresques - Op. 101 - B187

- Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum (Addison-Wesley Signature Series (Cohn))