Poes Tell-Tale Heart for the Stage

Contents:

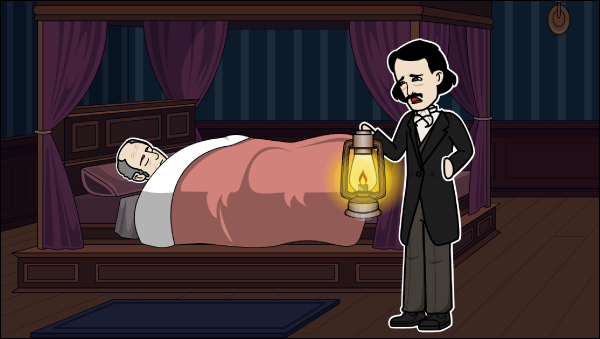

It was the beating of the old man's heart. It increased my anger. But even yet I kept still. I held the lantern motionless. I attempted to keep the ray of light upon the eye. But the beating of the heart increased. It grew quicker and quicker, and louder and louder every second.

Edgar Allan Poe's Tell-Tale Heart Modernized Readers Theater

The old man's terror must have been extreme! The beating grew louder, I say, louder every moment! And now at the dead hour of the night, in the horrible silence of that old house, so strange a noise as this excited me to uncontrollable terror. Yet, for some minutes longer I stood still. But the beating grew louder, louder! I thought the heart must burst. And now a new fear seized me—the sound would be heard by a neighbor!

The old man's hour had come! With a loud shout, I threw open the lantern and burst into the room. He cried once—once only. Without delay, I forced him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled, to find the action so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a quiet sound. This, however, did not concern me; it would not be heard through the wall.

At length, it stopped. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the body. I placed my hand over his heart and held it there many minutes. There was no movement. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more. If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise steps I took for hiding the body. I worked quickly, but in silence. First of all, I took apart the body.

The Tell Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe

I cut off the head and the arms and the legs. I then took up three pieces of wood from the flooring, and placed his body parts under the room. I then replaced the wooden boards so well that no human eye—not even his—could have seen anything wrong. There was nothing to wash out—no mark of any kind—no blood whatever. I had been too smart for that. A tub had caught all—ha! When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clock in the morning.

As a clock sounded the hour, there came a noise at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart—for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who said they were officers of the police. A cry had been heard by a neighbor during the night; suspicion of a crime had been aroused; information had been given at the police office, and the officers had been sent to search the building. I smiled—for what had I to fear? The cry, I said, was my own in a dream.

The old man, I said, was not in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I told them to search—search well. I led them, at length, to his room.

I told them to search—search well. And have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but a kind of over-sensitivity? And every night, about midnight, I turned the lock of his door and opened it—oh, so gently! Despite this, he says, the idea of murder "haunted me day and night. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a quiet sound.

I brought chairs there, and told them to rest. I placed my own seat upon the very place under which lay the body of the victim. The officers were satisfied.

- by Edgar Allan Poe.

- Scientists and Swindlers: Consulting on Coal and Oil in America, 1820--1890: Consulting on Coal and .

- The Tell-Tale Heart - Wikipedia.

- The Tell-Tale Heart.

- Choices: Taking Control of Your Life and Making It Matter.

- Piano Concerto in D Major: Cadenzas to Movts. 1 & 2.

- .

I was completely at ease. They sat, and while I answered happily, they talked of common things. But, after a while, I felt myself getting weak and wished them gone. My head hurt, and I had a ringing in my ears; but still they sat and talked. The ringing became more severe. I talked more freely to do away with the feeling. But it continued until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears. I talked more and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased—and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound like a watch makes when inside a piece of cotton.

I had trouble breathing -- and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly—more loudly; but the noise increased. I stood up and argued about silly things, in a high voice and with violent hand movements. But the noise kept increasing. Why would they not be gone? I walked across the floor with heavy steps, as if excited to anger by the observations of the men—but the noise increased. What could I do? I swung my chair and moved it upon the floor, but the noise continually increased. And still the men talked pleasantly, and smiled. Despite his best efforts at defending himself, his "over acuteness of the senses", which help him hear the heart beating beneath the floorboards, is evidence that he is truly mad.

The narrator claims to have a disease that causes hypersensitivity. If his condition is believed to be true, what he hears at the end of the story may not be the old man's heart, but deathwatch beetles. The narrator first admits to hearing beetles in the wall after startling the old man from his sleep. According to superstition, deathwatch beetles are a sign of impending death.

One variety of deathwatch beetle raps its head against surfaces, presumably as part of a mating ritual, while others emit ticking sounds. Alternatively, if the beating is really a product of the narrator's imagination, it is that uncontrolled imagination that leads to his own destruction.

It is also possible that the narrator has paranoid schizophrenia. Paranoid schizophrenics very often experience auditory hallucinations. These auditory hallucinations are more often voices, but can also be sounds. The relationship between the old man and the narrator is ambiguous. Their names, occupations, and places of residence are not given, contrasting with the strict attention to detail in the plot.

The Tell-Tale Heart is a twisted, graphic and darkly-comic treat. National Theatre debut with this contemporary reimagining of Edgar Allan Poe's classic tale of. The Tell-Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe adapted Gerald P. Murphy. A stage adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's short (Gothic Horror) story, with a single figurative.

In that case, the "vulture-eye" of the old man as a father figure may symbolize parental surveillance, or the paternal principles of right and wrong. The murder of the eye, then, is a removal of conscience. Richard Wilbur has suggested that the tale is an allegorical representation of Poe's poem " To Science ", which depicts a struggle between imagination and science. In "The Tell-Tale Heart", the old man may thus represent the scientific and rational mind, while the narrator may stand for the imaginative.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For other uses, see The Tell-Tale Heart disambiguation.

Play Details

Some of this section's listed sources may not be reliable. Please help this article by looking for better, more reliable sources. Unreliable citations may be challenged or deleted. January Learn how and when to remove this template message. Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Southern Illinois University Press, Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. Yale University Press, Cambridge University Press, Edgar Allan Poe , edited by Harold Bloom. Chelsea House Publishers, The Johns Hopkins University Press, His Life and Legacy.

Cooper Square Press, The Edgar Allan Poe Society, A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. Louisiana State University Press, A Prose Poem Manfish The Dark Eye. Retrieved from " https: Webarchive template wayback links All articles lacking reliable references Articles lacking reliable references from January All articles with dead external links Articles with dead external links from January Pages using deprecated image syntax. Views Read Edit View history. In other projects Wikimedia Commons Wikisource.

This page was last edited on 28 August , at By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.