Military Power, Conflict and Trade: Military Spending, International Commerce and Great Power Rivalr

Contents:

The two documents foreground strategic competition with the country, but Trump repeatedly over the last two years has said that he would like to get along with Vladimir Putin. The documents reflect the considered thinking of the U.

The demands posed by these changes on the state finances and economies differed. After the war, the European industrial and agricultural production amounted to only half of the total. These types of regimes have also been the most efficient economically, which has in turned reinforced the success of this fiscal regime model. The Japanese rearmament drive was perhaps the most impressive, with as high as Dependence on distant, often external suppliers of food limited the expansion of these empires.

They are little different from the strategy documents a Clinton administration would have published: Trump argues that the U. In January, the president announced new tariffs on imports of washing machines and solar panels at the request of domestic producers. Big business has far too much invested in international supply chains to withdraw from them now.

But much unites big business and the Trump administration. Of particular concern to both Trump and the Pentagon is that U. The administration will likely soon slap tariffs on Chinese steel on national security grounds: The Pentagon is demanding that Congress pass new appropriations for the military. Failure to do so, the Pentagon asserts in its Defense Strategy, will cost U.

The working class and poor will be made to suffer to pay for the ballooning U. We live in a dangerous world. The notion, popular in recent years, that we will never again see a war between large imperialist states — like we did in the 20th century, when established powers tried to crush their rivals at the cost of millions of lives — is badly mistaken.

The emerging great power rivalry now under way may involve some different actors from those that came before, but the consequences will be the same unless it is stopped in its tracks.

The return of great power rivalry

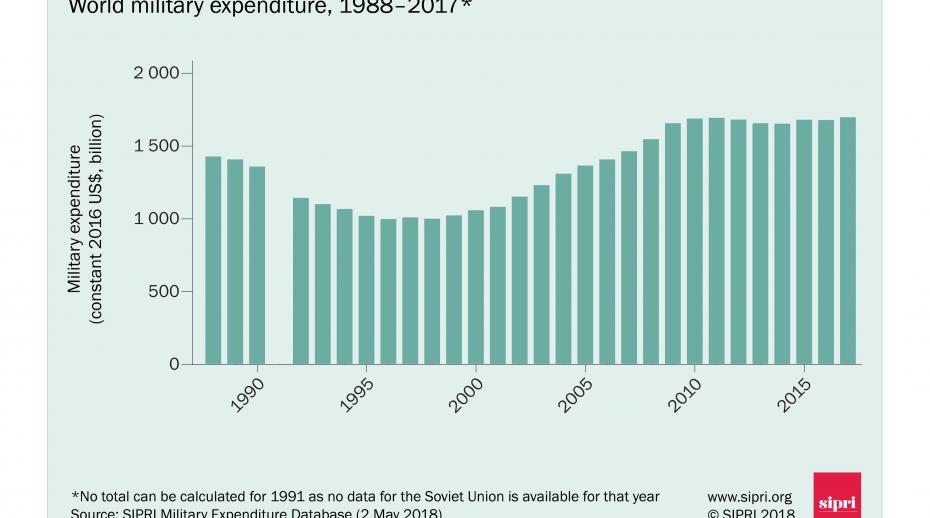

Posted Feb 06, by Tom Bramble Topics: Red Flag February 5, An apology for imperialism in a colourful package. Nomi Prins, how to set the economy on fire. All percentage changes are expressed in real terms constant prices. SIPRI monitors developments in military expenditure worldwide and maintains the most comprehensive, consistent and extensive data source available on military expenditure.

MR Online | The return of great power rivalry

Military expenditure refers to all government spending on current military forces and activities, including salaries and benefits, operational expenses, arms and equipment purchases, military construction, research and development, and central administration, command and support. World military spending — Military expenditure in South America rose by 4. Argentina up by 15 per cent and Brazil up by 6.

Armed forces were in turn used to maintain internal order. Societal unrest, inflation, and external incursions finally brought the Roman Empire, at least in the West, to an end.

U.S. AGGRESSION ON STEROIDS

During the Middle Ages, following the decentralized era of barbarian invasions, a varied system of European feudalism emerged, in which often feudal lords provided protection for communities for service or price. Since the Merovingian era, soldiers became more specialized professionals, with expensive horses and equipment. By the Carolingian era, military service had become largely the prerogative of an aristocratic elite. Prior to A. Also, in terms of science and inventions the Europeans were no match for these empires until the early modern period.

- Coordinating English at Key Stage 2 (Subject Leaders Handbooks)!

- Breadcrumb.

- Accessibility links.

- !

- Rebels on a Lost World - Book One (Book One - Tops Rebels)?

- Military Spending and the Early Empires;

- .

Moreover, it was not until the twelfth century and the Crusades that the feudal kings needed to supplement the ordinary revenues to finance large armies. Internal discontent in the Middle Ages often led to an expansionary drive as the spoils of war helped calm the elite — for example, the French kings had to establish firm taxing power in the fourteenth century out of military necessity.

The political ambitions of medieval kings, however, still relied on revenue strategies that catered to the short-term deficits, which made long-term credit and prolonged military campaigns difficult. Innovations in the ways of waging war and technology invented by the Chinese and the Islamic societies permeated Europe with a delay, such as the use of pikes in the fourteenth century and the gunpowder revolution of the fifteenth century, which in turn permitted armies to attack and defend larger territories.

This also made possible a commercialization of warfare in Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as feudal armies had to give way to professional mercenary forces. Accordingly, medieval states had to increase their taxation levels and tax collection to support the growing costs of warfare and the maintenance of larger standing armies.

Equally, the age of commercialization of warfare was accompanied by the rising importance of sea power as European states began to build their overseas empires as opposed to for example the isolationist turn of Ming China in the fifteenth century. These were also states that were economically cohesive due to internal waterways and small geographic size as well.

The early winners in the fight for world leadership, such as England, were greatly influenced by the availability of inexpensive credit, enabling them to mobilize limited resources effectively to meet military expenses. Their rise was of course preceded by the naval exploration and empire-building of many successful European states, especially Spain, both in Europe and around the globe. This pattern from command to commercialized warfare, from short-term to more permanent military management system, can be seen in the English case. In the period , the English defense share military expenditures as a percentage of central government expenditures averaged at However, in the period , the mean English defense share was This also reflected on the growing cost and scale of warfare: For example, Charles Tilly has estimated the battle deaths to have exceeded two million.

Henry Kamen, in turn, has emphasized the mass scale destruction and economic dislocation this caused in the German lands, especially to the civilian population.

Military Spending, International Commerce and Great Power Rivalry Michael P. a country's dependence on military power grows with its dependence on trade. mately, the shape and character of the global arms trade will be determined War had ended, great-power involve- ment in the least people during the entire conflict." "Major . World Military Expenditures and Arms. Transfers .. freed from superpower rivalry, it may .. Lethal Commerce: The Global Trade in Small.

With the increasing scale of armed conflicts in the seventeenth century, the participants became more and more dependent on access to long-term credit, because whichever government ran out of money had to surrender first. Therefore, the Spanish Crown defaulted repeatedly during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and on several occasions forced Spain to seek an end to its military activities.

Spain still remained one of the most important Great Powers of the period, and was able to sustain its massive empire mostly intact until the nineteenth century. What about other country cases — can they shed further light into the importance of military spending and warfare in their early modern economic and political development? A key question for France, for example, was the financing of its military exertions. This was due to both growth in the size of the army and the navy, and the decline in the purchasing power of the French livre.

The overall burden of war, however, remained roughly similar in this period: War expenditures accounted roughly 57 percent of total expenditure in , whereas they represented about 52 percent in Moreover, as for all the main European monarchies, it was the expenditure on war that brought fiscal change in France, especially after the Napoleonic wars.

Between and , there was a percent increase in French public expenditure and a consolidation of the emerging fiscal state. This also embodied a change in the French credit market structure. A success story, in a way a predecessor to the British model, was the Dutch state in this period. This financial regime lasted up until the end of the eighteenth century. Here again we can observe the intermarriage of military spending and the availability of credit, essentially the basic logic in the Ferguson model. One of the key features in the Dutch success in the seventeenth century was their ability to pay their soldiers relatively promptly.

The Dutch case also underlines the primacy of military spending in state budgets and the burden involved for the early modern states. As we can see in Figure 1, the defense share of the Dutch region of Groningen remained consistently around 80 to 90 percent until the mid-seventeenth century, and then it declined, at least temporarily during periods of peace. European State Finance Database. ESFD, [cited 1. Respectively, in the eighteenth century, with rapid population growth in Europe, armies also grew in size, especially the Russian army.

The new style of warfare brought on by the Revolutionary Wars, with conscription and war of attrition as new elements, can be seen in the growth of army sizes. For example, the French army grew over 3. Similarly, the British army grew from 57, in to , men in The Russian army acquired the massive size of , men in , and Russia also kept the size of its armed forces at similar levels in the nineteenth century.

However, the number of Great Power wars declined in number see Table 1 , as did the average duration of these wars. Yet, some of the conflicts of the industrial era became massive and deadly events, drawing in most parts of the world into essentially European skirmishes.

With the new kind of mobilization, which became more or less a permanent state of affairs in the nineteenth century, centralized governments required new methods of finance. The nineteenth century brought on reforms, such as centralized public administration, reliance on specific, balanced budgets, innovations in public banking and public debt management, and reliance on direct taxation for revenue. However, for the first time in history, these reforms were also supported with the spread of industrialization and rising productivity.

The nineteenth century was also the century of the industrialization of war, starting in the mid-century and gathering breakneck speed quickly. By the s, military engineering began to forge ahead of even civil engineering. Also, a revolution in transportation with steamships and railroads made massive, long-distance mobilizations possible, as shown by the Prussian example against the French in The demands posed by these changes on the state finances and economies differed.

Jari Eloranta, Appalachian State University

In the French case, the defense share stayed roughly the same, a little over 30 percent, throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whereas its military burden increased about one percent to 4. In the UK case, the defense share mean declined two percent to However, the strength of the British economy made it possible that the military burden actually declined a little to 2. However, the United States, the new economic leader by the closing decades of the century, averaged spending a meager 0.

As seen in Figure 2, the military burdens incurred by the Great Powers also varied in terms of timing, suggesting different reactions to external and internal pressures. Nonetheless, the aggregate, systemic real military spending of the period showed a clear upward trend for the entire period.

Moreover, the impact of the Russo-Japanese was immense for the total real spending of the sixteen states represented in the figure below, due to the fact that both countries were Great Powers and Russian military expenditures alone were massive. The unexpected defeat of the Russians unleashed, along with the arrival of dreadnoughts, an intensive arms race. With the beginning of the First World War in , this military potential was unleashed in Europe with horrible consequences, as most of the nations anticipated a quick victory but ended up fighting a war of attrition in the trenches.

Which country dominates the global arms trade?

Mankind had finally, even officially, entered the age of total war. As Table 2 displays, the French military burden was fairly high, in addition to the size of its military forces and the number of battle deaths. Therefore, France mobilized the most resources in the war and, subsequently, suffered the greatest losses.

The mobilization by Germany was also quite efficient, because almost the entire state budget was used to support the war effort. On the other hand, the United States barely participated in the war, and its personnel losses in the conflict were relatively small, as were its economic burdens. In comparison, the massive population reserves of Russia enabled fairly high personnel losses, quite similar to the Soviet experience in the Second World War.

Bureau of Census, ; Louis Fontvieille. Europe, , 4th edition, Basingstoke: Macmillan Academic and Professional, a; E. Morgan, Studies in British Financial Policy, David Singer and Melvin Small. National Material Capabilities Data, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, In the interwar period, the pre-existing tendencies to continue social programs and support new bureaucracies made it difficult for the participants to cut their public expenditure, leading to a displacement of government spending to a slightly higher level for many countries.

Public spending especially in the s was in turn very static by nature, plagued by budgetary immobility and standoffs especially in Europe. This meant that although in many countries, except the authoritarian regimes, defense shares dropped noticeably, their respective military burdens stayed either at similar levels or even increased — for example, the French military burden rose to a mean level of 7. In Great Britain also, the defense share mean dropped to For these countries, the mids marked the beginning of intense rearmament whereas some of the authoritarian regimes had begun earlier in the decade.

Germany under Hitler increased its military burden from 1. Mussolini was not quite as successful in his efforts to realize the new Roman Empire, with a military burden fluctuating between four and five percent in the s 5. The Japanese rearmament drive was perhaps the most impressive, with as high as For many countries, such as France and Russia, the rapid pace of technological change in the s rendered many of the earlier armaments obsolete only two or three years later.

There were differences between democracies as well, as seen in Figure 3. This was also similar to the actions of most East European states. Denmark was among the low-spending group, perhaps due to the futility of trying to defend its borders amidst probable conflicts involving giants in the south, France and Germany.

Overall, the democracies maintained fairly steady military burdens throughout the period. Their rearmament was, however, much slower than the effort amassed by most autocracies. This is also amply displayed in Figure 4. Eloranta , see especially appendices for the data sources. There are severe limitations and debates related to, for example, the German see e. Cambridge University Press, and the Soviet data see especially R.

Davies and Mark Harrison. In the ensuing conflict, the Second World War, the initial phase from to early favored the Axis as far as strategic and economic potential was concerned. For example, in the Allied total GDP was 2, billion international dollars in prices , whereas the Axis accounted for only billion. For example, Great Britain at the height of the First World War incurred a military burden of about 27 percent, whereas the military burden level consistently held throughout the Second World War was over 50 percent.

Cambridge University Press, ; Mitchell a ; B. The Americas, , fourth edition, London: The Soviet defense share only applies to years , whereas the military burden applies to These two measures are not directly comparable, since the former is measured in current prices and the latter in constant prices. As Table 3 shows, the greatest military burden was most likely incurred by Germany, even though the other Great Powers experienced similar levels. Only the massive economic resources of the United States made possible its lower military burden.

In this sense the Soviet Union fared the worst, and additionally the share of military personnel out of the population was relatively small compared to the other Great Powers.