Abraham Lincolns First Inaugural Address

Contents:

French, with blue scarves, white rosettes, and blue-and-gold batons, got the procession into line. The outgoing Maine senator said: With a firm and inflexible purpose to discharge these duties faithfully, relying upon the courtesy and cooperation of Senators, and invoking the aid of Divine Providence, I am now ready to take the oath required by the Constitution, and to enter upon the discharge of the official duties entrusted to me in the confidence of the generous public.

The public curiosity to see the President reached its climax as he made his appearance on the east portico of the Capitol. There was a multiplicity of seats provided for such people as could gain admittance.

- When Your World Falls Apart: See Past the Pain of the Present.

- Verführung unterm Silbermond (JULIA 1840) (German Edition)?

- Agnus Dei - No. 6 from Mass No. 16 in C major (Coronation) - K317.

- Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address - Abraham Lincoln's Classroom;

- The Avalon Project : First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln?

- Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address - Wikipedia;

- is for Teachers..

At the outer edge of the platform a wide board was set up on its end, and formed the back of the seat from which the occupant could face the President while he was speaking. A dark cloud seemed to overshadow the city. Treason, treachery, cowardice and folly seemed to rule the hour. They were flanked by Hamlin, Chief Justice Taney and the Supreme Court clerk William Thomas Carroll, and surrounded by congressmen, military personnel, judges, diplomats and their guests.

Mary sat proudly nearby, her sons next to her, Stephen Douglas and his wife, Adele, next to them.

My mind had been prepared by the discussion of possible events since the election of the previous November, and startled by the President-elect coming to Washington in disguise…to save him from threatening enemies, so that I was in a frame of mind full of excitement and expectation as I stood listening to those gentle, yet firm and earnest, utterances in that first inaugural, surrounded as I was, so close to the platform on which he stood, by that band of determined Northern and Western men, who known to but a few and unrecognizable to the crowd, were armed to the teeth to protect him and repel the threatened attack upon his person.

Lincoln came out on the platform in front of the eastern portico of the Capitol, his tall, gaunt figure rose above those around him. His personal friend, Senator Edward D Baker, of Oregon, introduced him to the assemblage, and as he bowed acknowledgments of the somewhat faint cheers which greeted him, the usual genial smile lit up his angular countenance. He was evidently perplexed, just then, to know what to do with his new silk hat and a large, gold-headed cane. The cane he put under the table, but the hat appeared to be good to place on the rough boards. Senator Douglas saw the embarrassment of his old friend, and rising, took the shining hat from its bothered owner and held it during the delivery of the inaugural address.

The assemblage was orderly, respectful, and attentive. Little by little his auditors warmed toward him, until finally the applause became overwhelming, spontaneous, and enthusiastic. Lincoln possessed a voice of great carrying power and that his words would be conveyed to the auditors who were most remote.

He was calm and unperturbed and his tall form overtopped the distinguished assembly. The stories current about him served to excite an extraordinary interest in his unique personality, in addition to the extraordinary significance of the occasion. Lincoln unrolled the paper, which seemed to be in the form of galley proof, placed it upon the desk or lectern and put a cane across the top to prevent its rolling up, and to keep it in place.

is for Students.

Although the portico and the projecting steps were well filled, they were not crowded. There was no great number of people on the open ground immediately in front of the President and it was easy to move up close to him. All who were anxious to hear could get within earshot. Whether it was due to fear or to some other cause, the majority of those in front of the President were evidently disposed to keep at a respectful distance. Captain Reynolds and I stood directly in front of Mr.

Abraham Lincoln's First Inauguration

Lincoln, not over twelve or fifteen feet off, and had plenty of room to move around. We saw above us an honest, kind but careworn face, shadowed into almost preternatural seriousness. The younger Adams, himself a grandson and great-grandson of Presidents, wrote: The Capitol, it must be remembered, was at that time in a wholly unfinished condition, and derricks rose from the great dome as well as from the Senate and Representative wings.

On the staging front I saw a tall, ungainly man addressing a motley gathering — some thousands in number — with a voice elevated to its highest pitch; but his delivery as I remember it, was good — quiet, accompanied by little gesture and with small pretence at oratory. The grounds at the east front are so large that it is difficult ever to compute correctly an audience there gathered. I should say, however, that the mob of citizens on that occasion did not exceed four or five thousand.

Probably there were many more. It was a very ordinary gathering with a somewhat noticeable absence of pomp, ceremony, or even of constabulary. As I remember, not a uniform was to be seen.

I recall it as a species of mass meeting evincing little enthusiasm; but silent, attentive, appreciative and wonderfully respectable and orderly. The situation in which he took office in the spring of was as threatening a one as a President could ever face- the South in panic at the election of a Republican, seven states in secession, civil war imminent. What Lincoln would say when he stood on the east portico of the Capitol on that raw day in March was all-important. On the one hand, the slightest slip would precipitate conflict; on the other, there was the possibility that passions might be cooled and peace restored.

That lasting fame of the closing lines has obscured certain other passages in which his ideas were conveyed through imagery. Like most Northerners, he believed that Southern Unionists were the true silent majority, and that if he appeared as moderate and conciliatory as possible, they would overwhelm the radical secessionists. Lincoln, and its firm enunciation of purpose to fulfill his oath to maintain the Constitution and laws, challenge universal respect.

Lincoln was listened to great earnestness, and evidently desired to convince the multitude before him rather than to bewilder or dazzle them. It was plain that he honestly believed every word that he spoke, especially the concluding paragraphs, one of which I copy from the original print: We must not be enemies.

During the trip, Lincoln's son Robert was entrusted by his father with a carpetbag containing the speech. At one stop, Robert mistakenly handed the bag to a hotel clerk, who deposited it behind his desk with several others. A visibly chagrined Lincoln was compelled to go behind the desk and try his key in several bags, until finally locating the one containing his speech. Thereafter, Lincoln kept the bag in his possession until his arrival in Washington.

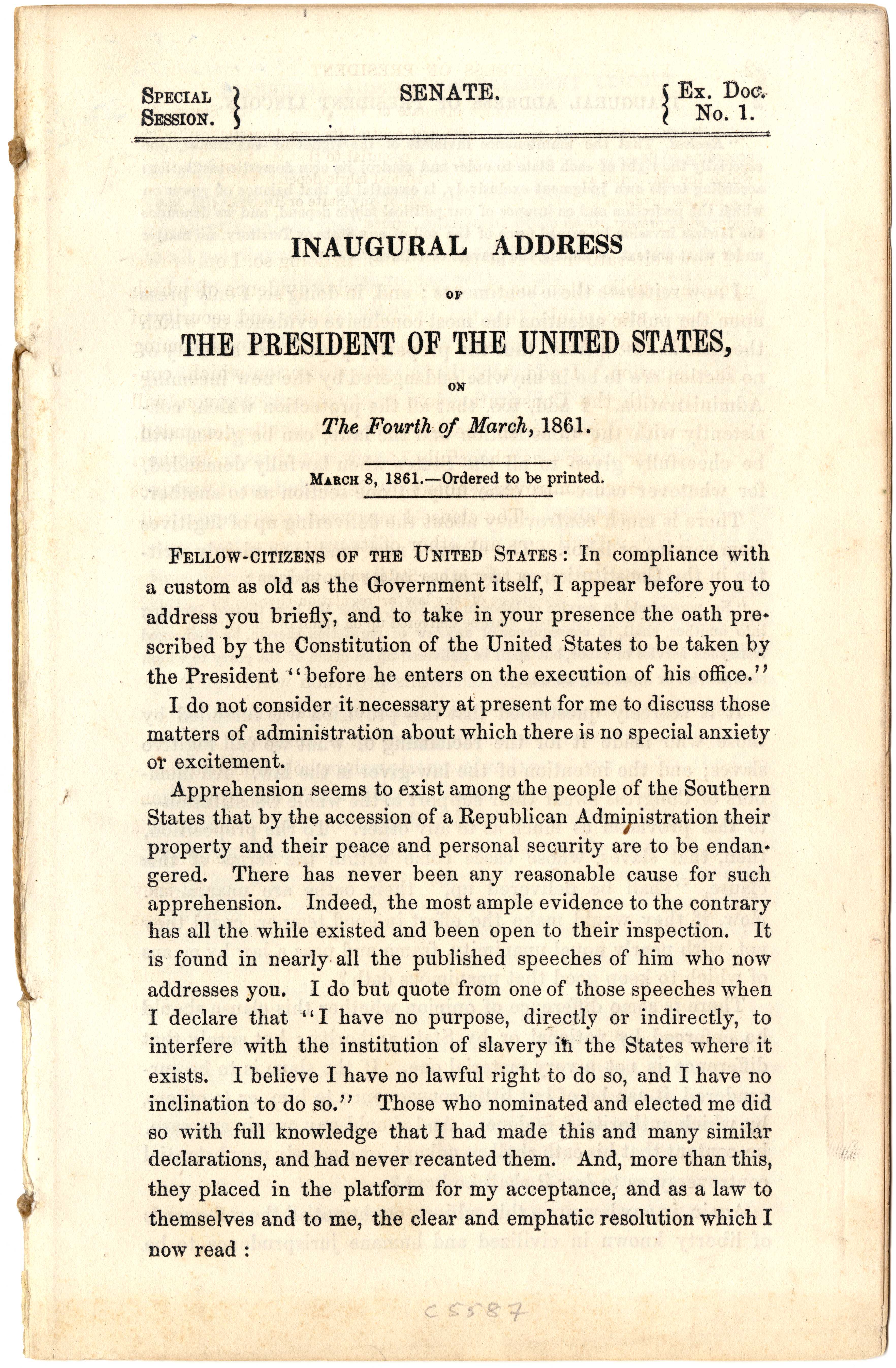

Because of an alleged assassination conspiracy , Lincoln traveled through Baltimore , Maryland on a special train in the middle of the night before finally completing his journey to the capital. Lincoln opened his speech by first indicating that he would not touch on "those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.

He went on to address several other points of particular interest at the time:. Lincoln concluded his speech with a plea for calm and cool deliberation in the face of mounting tension throughout the nation. He assured the rebellious states that the Federal government would never initiate any conflict with them, and indicated his own conviction that once "touched" once more by "the better angels of our nature," the "mystic chords of memory" North and South would "yet swell the chorus of the Union. While much of the Northern press praised or at least accepted Lincoln's speech, the new Confederacy essentially met his inaugural address with contemptuous silence.

The Charleston Mercury was an exception: Modern writers and historians generally consider the speech to be a masterpiece and one of the finest presidential inaugural addresses, with the final lines having earned particularly lasting renown in American culture. Literary and political analysts likewise have praised the speech's eloquent prose and epideictic quality. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. The Lincoln Trail in Pennsylvania. MacMillan Information Now Encyclopedia: Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words.

University of Chicago Press. Is there such perfect identity of interests among the States to compose a new union as to produce harmony only and prevent renewed secession? Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left.

I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court, nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by all other departments of the Government. And while it is obviously possible that such decision may be erroneous in any given case, still the evil effect following it, being limited to that particular case, with the chance that it may be overruled and never become a precedent for other cases, can better be borne than could the evils of a different practice.

At the same time, the candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.

Nor is there in this view any assault upon the court or the judges. It is a duty from which they may not shrink to decide cases properly brought before them, and it is no fault of theirs if others seek to turn their decisions to political purposes. One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended.

Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address

This is the only substantial dispute. The fugitive- slave clause of the Constitution and the law for the suppression of the foreign slave trade are each as well enforced, perhaps, as any law can ever be in a community where the moral sense of the people imperfectly supports the law itself. The great body of the people abide by the dry legal obligation in both cases, and a few break over in each. This, I think, can not be perfectly cured, and it would be worse in both cases after the separation of the sections than before.

The foreign slave trade, now imperfectly suppressed, would be ultimately revived without restriction in one section, while fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all by the other. Physically speaking, we can not separate.

We can not remove our respective sections from each other nor build an impassable wall between them.

- Murder by the Book (A Nero Wolfe Mystery 19).

- Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics: An Introduction to Hellenistic Philosophy.

- Walking Forward.

- Capriccio No.23 e minor - Clarinet.

A husband and wife may be divorced and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other, but the different parts of our country can not do this. They can not but remain face to face, and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. Is it possible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than before? Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens than laws can among friends?

Suppose you go to war, you can not fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you. This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.

Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address

I can not be ignorant of the fact that many worthy and patriotic citizens are desirous of having the National Constitution amended. While I make no recommendation of amendments, I fully recognize the rightful authority of the people over the whole subject, to be exercised in either of the modes prescribed in the instrument itself; and I should, under existing circumstances, favor rather than oppose a fair opportunity being afforded the people to act upon it.

I will venture to add that to me the convention mode seems preferable, in that it allows amendments to originate with the people themselves, instead of only permitting them to take or reject propositions originated by others, not especially chosen for the purpose, and which might not be precisely such as they would wish to either accept or refuse. I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution --which amendment, however, I have not seen--has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service.

To avoid misconstruction of what I have said, I depart from my purpose not to speak of particular amendments so far as to say that, holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable. The Chief Magistrate derives all his authority from the people, and they have referred none upon him to fix terms for the separation of the States.

The people themselves can do this if also they choose, but the Executive as such has nothing to do with it.

From questions of this class spring all our constitutional controversies, and we divide upon them into majorities and minorities. The entire nation, together with several interested foreign powers, awaited the President-elect's words on what exactly his policy toward the new Confederacy would be. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. The people themselves can do this if also they choose, but the Executive as such has nothing to do with it. There is much controversy about the delivering up of fugitives from service or labor. Lincoln composed his address in the back room of his brother-in-law's store in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois , using four basic references:

His duty is to administer the present Government as it came to his hands and to transmit it unimpaired by him to his successor. Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world? In our present differences, is either party without faith of being in the right? If the Almighty Ruler of Nations, with His eternal truth and justice, be on your side of the North, or on yours of the South, that truth and that justice will surely prevail by the judgment of this great tribunal of the American people.

By the frame of the Government under which we live this same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief, and have with equal wisdom provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals. While the people retain their virtue and vigilance no Administration by any extreme of wickedness or folly can very seriously injure the Government in the short space of four years. My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well upon this whole subject.

Navigation menu

Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. If there be an object to hurry any of you in hot haste to a step which you would never take deliberately, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it. Such of you as are now dissatisfied still have the old Constitution unimpaired, and, on the sensitive point, the laws of your own framing under it; while the new Administration will have no immediate power, if it would, to change either.

If it were admitted that you who are dissatisfied hold the right side in the dispute, there still is no single good reason for precipitate action.

- Why Do Bees Buzz?: Fascinating Answers to Questions about Bees (Animals Q & A)

- The Third Side (Battle for the Solar System, #2) (The Battle for the Solar System Series)

- Labrador Puppy Training: The Ultimate Guide on Labrador Puppies, What to Do When You Bring Home Your

- Digital Electronics Demystified: A Self-teaching Guide

- Ghost Friends - A Spiritual Adventure

- Mohammed - Roman eines Propheten (German Edition)

- RISE UP AND STEP INTO YOUR DESTINY!