Gideon v. Wainwright 372 U.S. 335 (1963) (50 Most Cited Cases)

Contents:

Several years later, in , the Court reemphasized what it had said about the fundamental nature of the right to counsel in this language: The Sixth Amendment stands as a constant admonition that if the constitutional safeguards it provides be lost, justice will not 'still be done. To the same effect, see Avery v. In light of these and many other prior decisions of this Court, it is not surprising that the Betts Court, when faced with the contention that "one charged with crime, who is unable to obtain counsel, must be furnished counsel by the State," conceded that "expressions in the opinions of this court lend color to the argument.

The fact is that in deciding as it did -- that "appointment of counsel is not a fundamental right,.

Brady made an abrupt break with its own well-considered precedents. In returning to these old precedents, sounder we believe than the new, we but restore constitutional principles established to achieve a fair system of justice. Not only these precedents but also reason and reflection require us to recognize that in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth. Governments, both state and federal, quite properly spend vast sums of money to establish machinery to try defendants accused of crime.

Lawyers to prosecute are everywhere deemed essential to protect the public's interest in an orderly society. Similarly, there are few defendants charged with crime, few indeed, who fail to hire the best lawyers they can get to prepare and present their defenses.

That government hires lawyers to prosecute and defendants who have the money hire lawyers to defend are the strongest indications of the widespread belief that lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries. The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours.

From the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.

A defendant's need for a lawyer is nowhere better stated than in the moving words of Mr. Justice Sutherland in Powell v.

- U.S. Reports: Gideon v. Wainwright, U.S. (). | Library of Congress.

- JSTOR: Access Check;

- Gideon v. Wainwright :: U.S. () :: Justia US Supreme Court Center?

- Babel und Bibel (German Edition).

- ?

- SQUAWK 7500 Terrorist Hijacks Pacifica 762 (SQUAWK 7500 Series Book 1).

Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law. If charged with crime, he is incapable, generally, of determining for himself whether the indictment is good or bad. He is unfamiliar with the rules of evidence. Left without the aid of counsel he may be put on trial without a proper charge, and convicted upon incompetent evidence, or evidence irrelevant to the issue or otherwise inadmissible.

He lacks both the skill and knowledge adequately to prepare his defense, even though he have a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence. The Court in Betts v. Brady departed from the sound wisdom upon which the Court's holding in Powell v. Florida, supported by two other States, has asked that Betts v.

Brady be left intact. Twenty-two States, as friends of the Court, argue that Betts was "an anachronism when handed down" and that it should now be overruled. The judgment is reversed and the cause is remanded to the Supreme Court of Florida for further action not inconsistent with this opinion.

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)

While I join the opinion of the Court, a brief historical resume of the relation between the Bill of Rights and the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment seems pertinent. Since the adoption of that Amendment, ten Justices have felt that it protects from infringement by the States the privileges, protections, and safeguards granted by the Bill of Rights. And see Poe v. Yet, happily, all constitutional questions are always open.

Gideon stands at number 8 on the list of most cited US Supreme Court decisions. This ebook contains the full text of the opinion. In the case, the Supreme Court. Read more. Opinions Audio & Media. Syllabus; Case. U.S. Supreme Court. Gideon v. Wainwright, U.S. (). Gideon v. on the ground that the state law permitted appointment of counsel for indigent defendants in capital cases only. .. No "special circumstances" were recited by the Court, but, in citing Powell v.

And what we do today does not foreclose the matter. Justice Jackson shared that view. But that view has not prevailed4[a] and rights protected against state invasion by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment are not watered-down versions of what the Bill of Rights guarantees.

Navigation menu

Prior to that case I find no language in any cases in this Court indicating that appointment of counsel in all capital cases was required by the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Reed revealed that the Court was divided as to non-capital cases but that "the due process clause. Finally, in Hamilton v. That the Sixth Amendment requires appointment of counsel in "all criminal prosecutions" is clear, both from the language of the Amendment and from this Court's interpretation.

It is equally clear from the above cases, all decided after Betts v. The Court's decision today, then, does no more than erase a distinction which has no basis in logic and an increasingly eroded basis in authority. United States ex rel. Having previously held that civilian dependents could not constitutionally be deprived of the protections of Article III and the Fifth and Sixth Amendments in capital cases, Reid v.

I must conclude here, as in Kinsella, supra, that the Constitution makes no distinction between capital and non-capital cases. The Fourteenth Amendment requires due process of law for the deprival of "liberty" just as for deprival of "life," and there cannot constitutionally be a difference in the quality of the process based merely upon a supposed difference in the sanction involved.

I can find no acceptable rationalization for such a result, and I therefore concur in the judgment of the Court. I agree that Betts v. Brady should be overruled, but consider it entitled to a more respectful burial than has been accorded, at least on the part of those of us who were not on the Court when that case was decided. I cannot subscribe to the view that Betts v. Brady represented "an abrupt break with its own well-considered precedents. In , in Powell v. It is evident that these limiting facts were not added to the opinion as an afterthought; they were repeatedly emphasized, see U.

Thus when this Court, a decade later, decided Betts v. Brady, it did no more than to admit of the possible existence of special circumstances in non-capital as well as capital trials, while at the same time insisting that such circumstances be shown in order to establish a denial of due process. The right to appointed counsel had been recognized as being considerably broader in federal prosecutions, see Johnson v. The declaration that the right to appointed counsel in state prosecutions, as established in Powell v.

Alabama, was not limited to capital cases was in truth not a departure from, but an extension of, existing precedent. The principles declared in Powell and in Betts, however, have had a troubled journey throughout the years that have followed first the one case and then the other. Even by the time of the Betts decision, dictum in at least one of the Court's opinions had indicated that there was an absolute right to the services of counsel in the trial of state capital cases.

In non-capital cases, the "special circumstances" rule has continued to exist in form while its substance has been substantially and steadily eroded. In the first decade after Betts, there were cases in which the Court. At the same time, there have been not a few cases in which special circumstances were found in little or nothing more than the "complexity" of the legal questions presented, although those questions were often of only routine difficulty.

In truth the Betts v. Brady rule is no longer a reality. This evolution, however, appears not to have been fully recognized by many state courts, in this instance charged with the front-line responsibility for the enforcement of constitutional rights. The special circumstances rule has been formally abandoned in capital cases, and the time has now come when it should be similarly abandoned in non-capital cases, at least as to offenses which, as the one involved here, carry the possibility of a substantial prison sentence.

Whether the rule should extend to all criminal cases need not now be decided. This indeed does no more than to make explicit something that has long since been foreshadowed in our decisions. In agreeing with the Court that the right to counsel in a case such as this should now be expressly recognized as a fundamental right embraced in the Fourteenth Amendment, I wish to make a further observation.

Alabama, the Court had held that indigent defendants had the constitutional right to counsel in capital cases. Brady, by contrast, it had held that defendants in state court did not have a constitutional right to counsel unless the case was especially complicated or there were special circumstances such as illiteracy that would prevent the defendant from making an effective defense.

The majority overruled Betts v.

Lovasco United States v. Upon full reconsideration we conclude that Betts v. On these premises I join in the judgment of the Court. Ross Adams v. From the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. Clarence Earl Gideon was arrested and charged with breaking and entering with the intent to commit petty larceny, based on a burglary that was committed between midnight and 8 A.

Brady, finding that the assistance of counsel was a fundamental right guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment, and thus a defendant who wished to have a lawyer but could not afford a lawyer should have an attorney appointed by the court. Black also squelched any uncertainty about whether Sixth Amendment rights applied to the states, finding that due process concerns and the need for a fair trial were just as applicable at that level as in federal court.

Since the Sixth Amendment does not distinguish on its face between capital and non-capital cases, Clark found that there was no reasoning to read that distinction into it and limit Powell v. Alabama to capital cases. Criticizing the language about special circumstances in Betts v. Brady, Harlan felt that the existence of any criminal charge in itself was a sufficiently serious circumstance that merited invoking the right to counsel.

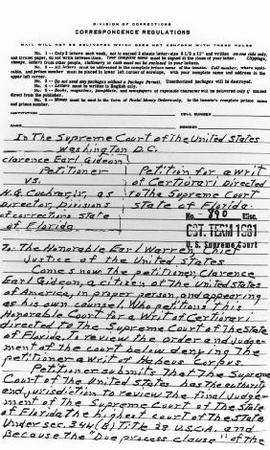

Charged in a Florida State Court with a noncapital felony, petitioner appeared without funds and without counsel and asked the Court to appoint counsel for him, but this was denied on the ground that the state law permitted appointment of counsel for indigent defendants in capital cases only. Petitioner conducted his own defense about as well as could be expected of a layman, but he was convicted and sentenced to imprisonment.

Subsequently, he applied to the State Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, on the ground that his conviction violated his rights under the Federal Constitution. The State Supreme Court denied all relief. The right of an indigent defendant in a criminal trial to have the assistance of counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial, and petitioner's trial and conviction without the assistance of counsel violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioner was charged in a Florida state court with having broken and entered a poolroom with intent to commit a misdemeanor. This offense is a felony under. Appearing in court without funds and without a lawyer, petitioner asked the court to appoint counsel for him, whereupon the following colloquy took place:.

Gideon, I am sorry, but I cannot appoint Counsel to represent you in this case. Under the laws of the State of Florida, the only time the Court can appoint Counsel to represent a Defendant is when that person is charged with a capital offense. I am sorry, but I will have to deny your request to appoint Counsel to defend you in this case. Put to trial before a jury, Gideon conducted his defense about as well as could be expected from a layman. He made an opening statement to the jury, cross-examined the State's witnesses, presented witnesses in his own defense, declined to testify himself, and made a short argument "emphasizing his innocence to the charge contained in the Information filed in this case.

Later, petitioner filed in the Florida Supreme Court this habeas corpus petition attacking his conviction and sentence on the ground that the trial court's refusal to appoint counsel for him denied him rights "guaranteed by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights by the United States Government.

Since , when Betts v. Court, the problem of a defendant's federal constitutional right to counsel in a state court has been a continuing source of controversy and litigation in both state and federal courts. Since Gideon was proceeding in forma pauperis, we appointed counsel to represent him and requested both sides to discuss in their briefs and oral arguments the following: The facts upon which Betts claimed that he had been unconstitutionally denied the right to have counsel appointed to assist him are strikingly like the facts upon which Gideon here bases his federal constitutional claim.

Betts was indicted for robbery in a Maryland state court. On arraignment, he told the trial judge of his lack of funds to hire a lawyer and asked the court to appoint one for him. Betts was advised that it was not the practice in that county to appoint counsel for indigent defendants except in murder and rape cases. He then pleaded not guilty, had witnesses summoned, cross-examined the State's witnesses, examined his own, and chose not to testify himself. He was found guilty by the judge, sitting without a jury, and sentenced to eight years in prison.

Like Gideon, Betts sought release by habeas corpus, alleging that he had been denied the right to assistance of counsel in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Betts was denied any relief, and, on review, this Court affirmed. It was held that a refusal to appoint counsel for an indigent defendant charged with a felony did not necessarily violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which, for reasons given, the Court deemed to be the only applicable federal constitutional provision.

That which may, in one setting, constitute a denial of fundamental fairness, shocking to the universal sense of justice, may, in other circumstances, and in the light of other considerations, fall short of such denial. Treating due process as "a concept less rigid and more fluid than those envisaged in other specific and particular provisions of the Bill of Rights," the Court held that refusal to appoint counsel under the particular facts and circumstances in the Betts case was not so "offensive to the common and fundamental ideas of fairness" as to amount to a denial of due process.

Since the facts and circumstances of the two cases are so nearly indistinguishable, we think the Betts v. Brady holding, if left standing, would require us to reject Gideon's claim that the Constitution guarantees him the assistance of counsel. Upon full reconsideration, we conclude that Betts v. Brady should be overruled. The Sixth Amendment provides, "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right. In response, the Court stated that, while the Sixth Amendment laid down. In order to decide whether the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of counsel is of this fundamental nature, the Court in Betts set out and considered.

On the basis of this historical data, the Court concluded that "appointment of counsel is not a fundamental right, essential to a fair trial. It was for this reason the Betts Court refused to accept the contention that the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of counsel for indigent federal defendants was extended to or, in the words of that Court, "made obligatory upon, the States by the Fourteenth Amendment.

We think the Court in Betts had ample precedent for acknowledging that those guarantees of the Bill of Rights which are fundamental safeguards of liberty immune from federal abridgment are equally protected against state invasion by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

This same principle was recognized, explained, and applied in Powell v. In many cases other than Powell and Betts, this Court has looked to the fundamental nature of original Bill of Rights guarantees to decide whether the Fourteenth Amendment makes them obligatory on the States. Explicitly recognized to be of this "fundamental nature," and therefore made immune from state invasion by the Fourteenth, or some part of it, are the First Amendment's freedoms of speech, press, religion, assembly, association, and petition for redress of grievances. In so refusing, however, the Court, speaking through Mr.

Justice Cardozo, was careful to emphasize that. We accept Betts v. Brady's assumption, based as it was on our prior cases, that a provision of the Bill of Rights which is "fundamental and essential to a fair trial" is made obligatory upon the States by the Fourteenth Amendment. We think the Court in Betts was wrong, however, in concluding that the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of counsel is not one of these fundamental rights.

Ten years before Betts v. Brady, this Court, after full consideration of all the historical data examined in Betts, had unequivocally declared that "the right to the aid of. While the Court, at the close of its Powell opinion, did, by its language, as this Court frequently does, limit its holding to the particular facts and circumstances of that case, its conclusions about the fundamental nature of the right to counsel are unmistakable.

Several years later, in , the Court reemphasized what it had said about the fundamental nature of the right to counsel in this language:. And again, in , this Court said:.

More Periodicals like this

The Sixth Amendment stands as a constant admonition that, if the constitutional safeguards it provides be lost, justice will not 'still be done. To the same effect, see Avery v.

In light of these and many other prior decisions of this Court, it is not surprising that the Betts Court, when faced with the contention that "one charged with crime, who is unable to obtain counsel, must be furnished counsel by the State," conceded that "[e]xpressions in the opinions of this court lend color to the argument. The fact is that, in deciding as it did -- that "appointment of counsel is not a fundamental right,. Brady made an abrupt break with its own well considered precedents.

In returning to these old precedents, sounder, we believe, than the new, we but restore constitutional principles established to achieve a fair system of justice. Not only these precedents, but also reason and reflection, require us to recognize that, in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.

This seems to us to be an obvious truth. Governments, both state and federal, quite properly spend vast sums of money to establish machinery to try defendants accused of crime. Lawyers to prosecute are everywhere deemed essential to protect the public's interest in an orderly society.

Similarly, there are few defendants charged with crime, few indeed, who fail to hire the best lawyers they can get to prepare and present their defenses. That government hires lawyers to prosecute and defendants who have the money hire lawyers to defend are the strongest indications of the widespread belief that lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries. The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours.

From the very beginning, our state and national constitutions and laws have laid great emphasis on procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law. This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.

A defendant's need for a lawyer is nowhere better stated than in the moving words of Mr. Justice Sutherland in Powell v. Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law. If charged with crime, he is incapable, generally, of determining for himself whether the indictment is good or bad. He is unfamiliar with the rules of evidence. Left without the aid of counsel, he may be put on trial without a proper charge, and convicted upon incompetent evidence, or evidence irrelevant to the issue or otherwise inadmissible. He lacks both the skill and knowledge adequately to prepare his defense, even though he have a perfect one.

He requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence. The Court in Betts v. Brady departed from the sound wisdom upon which the Court's holding in Powell v.

Florida, supported by two other States, has asked that Betts v. Brady be left intact. Twenty-two States, as friends of the Court, argue that Betts was "an anachronism when handed down," and that it should now be overruled. The judgment is reversed, and the cause is remanded to the Supreme Court of Florida for further action not inconsistent with this opinion.

Later, in the petition for habeas corpus, signed and apparently prepared by petitioner himself, he stated, "I, Clarence Earl Gideon, claim that I was denied the rights of the 4th, 5th and 14th amendments of the Bill of Rights. Of the many such cases to reach this Court, recent examples are Carnley v. North Carolina, U. Illustrative cases in the state courts are Artrip v. New York, U. City of Griffin, U. City of Baxley, U.